The guardianship pages include a discussion of both guardianships (guardian of the person) and conservatorships (guardian of the estate). Examples of model practices are provided throughout each section. Information and resources are provided on the following topics.

Guardianship is a relationship created by state law in which a court gives one person or entity (the guardian) the duty and power to make personal and/or property decisions for another (the ward). Guardianships were designed to protect the interest of incapacitated adults and elders in particular. Specific guardianship terminology varies from state to state. Generally agreed upon terms are provided below:

- A Guardian is an individual or an organization named by the court order to exercise some or all powers over the person and/or the estate of an individual.

- A Guardian of the Person is a guardian who possesses some or all power with regard to the personal affairs of the individual.

- A Guardian of the Estate is a guardian who possesses some or all powers with regard to the real and personal property of the individual (often referred to as conservators or fiduciaries).

Due to the seriousness of the loss of individual rights, guardianships are considered to be an option of "last resort." The court can order either a full (plenary) or limited guardianship for incapacitated persons. Under full guardianship, wards relinquish all rights to self-determination and guardians have full authority over their wards' personal and financial affairs: Wards lose all fundamental rights, including the right to manage their own finances, buy or sell property, make medical decisions for themselves, get married, vote in elections, and enter into contracts. For this reason, limited guardianships—in which the guardian's powers and duties are limited so that wards retain some rights depending on their level of capacity—are preferred.

Courts rely on a variety of types of guardians, including private and professional individuals and entities. Courts prefer to appoint a family member to act as guardian over an incapacitated relative, but it is not always possible to find family members or friends to take on this responsibility. In recent years, an entire service industry of private professional guardians has grown out of the increasing demand for guardians. In addition, most states have a public guardianship program, funded by state or local governments, to serve incapacitated adults who do not have the means to pay for the costs associated with guardianship and do not have family or friends who can serve in a guardianship capacity.

Resources

The Wingspread Era

In 1987, the Associated Press published a series of articles (Guardians of the Elderly: An Ailing System) following its examination of 2,200 randomly selected guardianship court files. The AP report denounced the nation's guardianship system as "a dangerously burdened and troubled system that regularly puts elderly lives in the hands of others with little or no evidence of necessity, then fails to guard against abuse, theft and neglect" (Bayles and McCartney, 1987).

The 1987 AP series, as well as a 1988 National Guardianship Symposium (the "Wingspread Conference") sponsored by the American Bar Association (ABA) prompted a hearing by the U.S. House Committee on Aging. State legislatures throughout the country responded by passing a number of guardianship measures. State reforms featured five key trends: (1) stronger procedural protections for alleged incapacitated persons, (2) a more functional determination of incapacity, (3) use of limited guardianship and emphasis on the principle of the "least restrictive alternative", (4) stronger court monitoring, and (5) development of public guardianship programs (see Wards of the State).

In the late 1980s and 1990s, a host of national, state, and local efforts sought to strengthen guardianship practice (see Guardian Accountability: Then and Now). Major events include the following:

- The National Guardianship Association was created in 1987 and produced Standards of Practice and a Code of Ethics.

- A study by the American Bar Association profiled best practices in guardianship monitoring. (The ABA and AARP updated the study in 2006.)

- Legal Counsel for the Elderly Inc., at AARP, coordinated the National Guardianship Monitoring Program, which used trained volunteers to be the "eyes and ears" of the court.

- The National Probate Court Standards was released and included standards related to procedural protections, limited guardianships, use of less restrictive guardianship alternatives, and court procedures to monitor guardian activities.

- The Uniform Guardianship and Protective Proceedings Act was revised in 2007.

The Wingspan Conference

In 2001, seven national groups convened a second national guardianship conference ("Wingspan"), resulting in a set of recommendations for action. Additionally in 2001, the first National Summit on Elder Abuse called elder abuse "a crisis requiring full mobilization." Two years later the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging held hearings on guardianship, the first in a decade, entitled "Guardianships Over the Elderly: Security Provided or Freedoms Denied?" The hearing profiled cases of misuse of guardianship.

In 2004, the Government Accountability Office released a report on guardianships that noted the lack of cooperation between courts and federal agencies "…that may leave incapacitated people without the protection of responsible guardians and representative payees." In September 2006, the continuation of problems with guardianships was highlighted by the United States Senate Special Committee on Aging. Committee hearings "brought to light the continuing failure of guardianship to protect the elderly from physical neglect and abuse, financial exploitation, and indignity." In November 2018, the Special Committee on Aging released Guardianship for the Elderly, and called for "the development of promising new models for guardianship for the elderly."

Third National Guardianship Summit

The National Guardianship Network (NGN)* convened the Third National Guardianship Summit in October 2011, the tenth anniversary of the historic 2001 Wingspan conference. Held in Salt Lake City at the University of Utah's S.J. Quinney College of Law, the Summit was a multi-disciplinary consensus conference that focused on post-appointment guardian performs and decision-making. The Summit delegates passed a number of substantive and sweeping recommendations for standards for decision-making for all guardians. The final version of the Guardian Standards and Recommendations for Action were released in spring 2012. A series of commissioned papers was published in Summer 2019 issue of the Utah Law Review. Among the Summit’s recommendations were the creation of WINGS—Working Interdisciplinary Networks of Guardianship Stakeholders. Sponsored by the National Guardianship Network, four states (New York, Oregon, Texas and Utah) received small grants to create WINGS. Their experiences can be found in the State Replication Guide for Working Interdisciplinary Networks of Guardianship Stakeholders.

Recent Court Efforts

State court leadership began a concerted effort in the latter part of the decade to address guardianship issues. In 2008, with funding from the Retirement Research Foundation of Chicago, the National Center for State Courts created the Center for Elders and the Courts (CEC). The CEC provides resources for courts on aging issues, elder abuse, and guardianship. In 2009, the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) and the Conference of State Court Administrators (COSCA) created a Joint Task Force on Elders and the Courts. In 2010, the Joint Task Force issued a report on guardianship data and issues, which put forward a number of recommendations. Also, in 2010, COSCA selected the topic of guardianships as the focus of their White Paper. In 2011, the CCJ/COSCA Joint Task Force became a standing committee. In 2013, the National College of Probate Judges released new Probate Court Standards, which were recently endorsed by the Conference of Chief Justices .

Ongoing Challenges

Ongoing challenges associated with guardianships continue to be highlighted in local media stories and state and local inquiries. For example, in 2010, at the request of the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, the GAO investigated the financial exploitation, neglect and abuse of seniors in the guardianship system. GAO investigators focused on 20 cases in which guardians stole or improperly obtained assets from incapacitated victims. In the majority of these cases, the GAO found that the potential guardians were inadequately screened and there was insufficient oversight of guardians after appointment. Furthermore, the GAO, using fictitious identities, obtained guardianship certifications or met certification requirements in four separate states. None of the courts or certification organizations used by those states checked the credit history or validated the Social Security numbers of the fictitious applicants. The investigation suggested that little had changed to protect incapacitated seniors since the GAO's 2004 report on guardianships.

In 2011, the National Center for State Courts provided testimony to the U.S. Senate on Protecting Seniors and Persons with Disabilities – An Examination of Court-Appointed Guardians. The testimony notes the need for reliable data and electronic filing systems, and supports proposed legislation that would create and fund a Guardianship Court Improvement Program (GCIP) that would improve court processes and outcomes for protected persons.

Resources

- Guardianship of the Elderly: Past Performance and Future Promises

- Adult Guardianships: A "Best Guess" National Estimate and the Momentum for Reform

- State Replication Guide for Working Interdisciplinary Networks of Guardianship Stakeholders

*The National Guardianship Network is comprised of the American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging, American Bar Association Section of Real Property, Trust and Estate Law, the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel, the Center for Guardianship Certification, the National Academy of Elder Law Attorneys, the National Center for State Courts, the National College of Probate Judges, and the National Guardianship Association.

A number of state task forces have been created to respond to problems in the guardianship and conservatorship court processes. Task forces tend to be created only after highly critical media reports highlighting individual cases that typically involve the abuse or financial exploitation of protected persons by their guardian/conservator. The following offers a summary of more recent state task force activities.

Arizona

In 2010, the Arizona Supreme Court established the Committee on Improving Judicial Oversight and Processing of Probate Matters. The Committee released its Final Report in 2011. Many of the Committee’s recommendations have since been put into place through legislation (see Judge Mroz’s PowerPoint presentation for an overview of statutory changes). Recommendations offered by the Committee follow.

The Supreme Court should… | |

|---|---|

Recommendation 1 | Advocate for the legislature to expand the statutory “standby” guardianship provisions in the probate code. |

Recommendation 2 | Advocate for the legislature to include a statutory provision in the probate code that exclusively applies to incapacitated minors approaching adulthood. |

Recommendation 3 | Add a rule to the Probate Rules that requires funded, ongoing, unannounced post-appointment visitation of wards and protected persons. |

Recommendation 4 | Add a Probate Rule directing the superior court to create and conduct a funded program for random audits of conservatorship accountings to validate the accuracy of annual or biennial accounts currently required in all adult conservatorship matters. |

Recommendation 5 | Explore funding sources for conducting periodic visitations, reporting, training, and random audits. |

Recommendation 6 | Develop statewide uniform training requirements for major participants in guardianship and conservatorship cases in specified ways. |

Recommendation 7 | Give priority to the development of automated case management systems that will substantially improve probate case monitoring and oversight by efficient and cost-effective means. |

| Recommendation 8 | Develop uniform, interactive and dynamic electronic probate forms through AZTurboCourt or another online website that will allow documents to be electronically generated and filed. The court should prioritize phasing in AZTurboCourt for probate matters. |

| Recommendation 9 | Adopt statewide fee guidelines for attorneys and fiduciaries paid from an estate. |

| Recommendation 10 | Add a Probate Rule or ask the legislature to include a statutory provision in the probate code, that requires attorneys, fiduciaries and others seeking fees from an estate in guardianship or conservatorship cases to do so within a specific time frame or be barred from doing so, absent good cause. |

| Recommendation 11 | Ask the legislature to adopt a fee-shifting statute specifically applicable to probate matters. The court should also promulgate a corresponding Probate Rule. |

| Recommendation 12 | Ask the legislature to adopt a statute mandating arbitration for disputes concerning the reasonableness of fees of fiduciaries and all attorneys paid from the estate. |

California

In 2006, the California Supreme Court created the Probate Conservatorship Task Force to make recommendations to the Judicial Council for reforms and improvements to the conservatorship process. The task force’s final report was submitted to the Judicial Council in 2007 and includes 85 recommendations. In 2008, the Administrative Director of the Courts noted the implementation status of each recommendation. Several laws have been passed based on the task force’s recommendations; however, California’s budget crisis has impacted the ability of the courts to make the necessary reforms to the conservatorship system.

Nebraska

In 2010, the Nebraska Supreme Court created the Joint Review Committee on the Status of Adult Guardianships and Conservatorships in the Nebraska Court System. The Committee issued its final report in 2010. Based on these recommendations, the legislature passed a number of laws that give the Nebraska courts new tools to assess the qualifications of prospective guardians and conservators for vulnerable persons, accurately document and track the assets of protected persons, and rigorously monitor the performance of guardians and conservators throughout the duration of their appointments.

Committee recommendations were divided into three categories: (1) changes that can be implemented with little or no fiscal impact; (2) changes that can be implemented over time but may require increased funding; and (3) systemic restructuring that requires further study. The final report included recommendations for the Supreme Court, the State Court Administrator, and the judiciary. The Supreme Court recommendations are offered below.

The Supreme Court should… | |

|---|---|

Recommendation 1 | Review and adopt forms to be used in all guardian and/or conservator cases statewide. |

Recommendation 2 | Adopt a court rule or support a statutory change regarding required local and federal background checks including Abuse and Neglect Registries, Adult Protective Services and Child Protective Services findings, and credit checks. |

Recommendation 3 | Adopt a court rule requiring that filing requirements for guardians and conservators be included on their Letters. |

Recommendation 4 | Adopt a court rule requiring all courts to hand out the Quick Reference Guide with sample forms attached to guardians and conservators with their Letters. |

Recommendation 5 | Adopt a court rule requiring that inventories be sent, by certified mail and regular mail, to all interested parties. |

Recommendation 6 | Adopt a court rule requiring courts/clerks to make sure all interested parties are on the Affidavit of Mailing for the inventories, annual accounting, and condition of ward reports that are filed with the court. |

Recommendation 7 | Adopt a court rule requiring that all accountings be reviewed by auditors. |

Recommendation 8 | Adopt a court rule requiring the Statement of Assets that is filed with the Accounting be reviewed by an auditor or probate supervisor and/or magistrate to determine if the bond previously set is adequate. |

Recommendation 9 | Adopt a court rule requiring bank statements and brokerage reports to be submitted with all accountings. |

Recommendation 10 | Adopt a court rule or support amendments to existing statute to require inventories be filed in guardianship cases. |

Recommendation 11 | Adopt a court rule or support a statutory change to require inventories to be filed in guardianship and/or conservatorship cases within 30 days of appointment. |

Recommendation 12 | Adopt a court rule requiring all initial inventories filed with the court be reviewed by the judge to determine if a bond needs to be set and/or the previously set bond is adequate. |

Recommendation 13 | Adopt a court rule requiring the guardian and/or conservator to file their Letters with the Register of Deeds in any county where the ward has real property or an interest in real property. |

Recommendation 14 | Adopt a court rule requiring an updated inventory be filed every year and it should be reviewed by the auditor or the judge to determine if the bond is still sufficient. |

Recommendation 15 | Adopt a court rule requiring that in the absence of any interested parties, the court should appoint a Guardian Ad Litem for the ward. |

Recommendation 16 | Adopt a court rule prohibiting ATM withdrawals or cash back on debit transactions without prior court approval. |

Recommendation 17 | Adopt a court rule requiring guardians and conservators to register with the central database each case they are appointed on. |

Recommendation 18 | Further study the need to enhance and implement regular judicial education for both judges and court staff on the full range of complexity of guardianship and conservatorship cases. |

Recommendation 19 | Establish a standing commission to focus on guardian and conservator issues, including further study emerging best practices for court case management to address the relevant interests of protecting vulnerable adults’ wellbeing and estate and property; judicial specialization and rotation; docket timeliness and management; court monitoring and auditing; and economic, geographical, and case volume conditions. |

South Carolina

In 2009, the South Carolina Supreme Court Chief Justice created the Task Force on State Courts and the Elderly to “study and make recommendations to the Supreme Court to improve court responses to elder abuse, adult guardianships and conservatorships.” The final report was issued in 2010. The Task Force’s recommendations follow:

- That the Supreme Court replace the Task Force with a Commission on State Courts and the Elderly;

- That the Commission emphasize a variety of non-legislative strategies to the extent practicable in effecting necessary or desirable change;

- That the Commission adopt a philosophy of “agile management” characterized by use of “moving target” goals; pilot and demonstration programs; process re-engineering; and innovative funding and staffing arrangements;

- That the Commission undertake a program to educate and build consensus among the judiciary, the bar, other court constituencies, state and county officials, nongovernmental service organizations, and the public.

Utah

In Utah, the Ad Hoc Committee on Probate Law and Procedure submitted its final report to the Utah Judicial Council in 2009. The committee’s recommendations follow:

- Modernize the definition of incapacity to focus on functional limitations. Require proof of incapacity (among other grounds) to appoint a conservator or a guardian.

- Enforce the requirement to prove incapacity by clear and convincing evidence.

- Consider in every case ordering that the respondent be evaluated by a physician or psychiatrist and by a court visitor. Adopt uniform forms on which to report the results of a clinical and social evaluation.

- Appoint a lawyer to represent the respondent in conservatorship cases, as is now done in guardianship cases.

- Require the respondent’s lawyer to be from a roster of qualified lawyers maintained by the Utah State Bar. Establish minimum qualifications for the roster. Appropriate funds to pay the respondent’s lawyer if the respondent cannot afford a lawyer and does not qualify for existing programs.

- Respondent’s lawyer should be an independent and zealous advocate, rather than a guardian ad litem.

- If the court determines that a petition resulted in an order beneficial to the respondent, and if funds are available in the estate, permit the court or conservator to pay the reasonable and necessary expenses, costs and attorney fees from the estate.

- Require the respondent to attend all hearings unless the respondent waives that right or unless the court finds that attending the hearing would harm the respondent. Take steps to accommodate the special needs of respondents at court hearings.

- Appoint a certified court interpreter if the respondent does not understand English.

- Refer protective proceedings to mediation. The mediation community should develop training for mediating protective proceedings, including especially the skills and accommodations necessary when mediating with a person of potentially diminished capacity.

- Consider appointing a commissioner to hear probate matters, including guardianship and conservatorship cases, in districts with sufficient caseload.

- With a few exceptions, classify guardianship and conservatorship records as private.

- Require the petitioner to show that alternatives less restrictive than appointing a fiduciary have failed or that they would not be effective. Presume, rather than favor, limited guardianships. Adopt laws, procedures and forms that make limited guardianships a realistic option.

- Require the fiduciary to use the “substituted judgment” standard for decision making on behalf of the respondent except in those limited circumstances in which the “best interest” standard may be used.

- Adopt special procedures for temporary emergency appointments.

- Eliminate “school guardianships.”

- Permit a person to nominate, rather than appoint, a guardian for self, a child or a spouse, and to petition to confirm the nomination during one’s lifetime.

- Require the fiduciary to write a management plan and file it with the court.

- Appoint a coordinator to develop a program of volunteer court visitors.

- Regulate the profession of guardian through the Division of Occupational and Professional licensing. Require private guardians and conservators to disclose any criminal convictions that have not been expunged.

- Develop training for lawyers, judges and court staff. Develop outreach and assistance to guardians, conservators, respondents and the public.

- Unify the laws regulating guardians and conservators except where there is sound policy to differentiate them.

Adult guardianship is a matter of state law. Guardianship laws typically are part of a state's laws on probate, trusts, estates and/or fiduciaries. The Uniform Law Commission has promulgated three pieces of model legislation that have had significant influence on the development and evolution of state guardianship law: the Uniform Probate Code, the Uniform Guardianship and Protected Proceedings Act and the Uniform Adult Guardianship and Protected Proceedings Jurisdiction Act.

The Uniform Probate Code (UPC), first approved in 1969 and revised several times since, was one of the earliest efforts to promote uniformity of state family property laws. UPC Article 5 pertains to guardianship proceedings. Other articles of the UPC address the succession of property through intestacy, wills, trusts, and other legal mechanisms for the transfer of property. As of June 2012, 18 states and the U.S. Virgin Islands have enacted the UPC, and most states have adopted or adapted portions of the code.

UPC Article 5 was revised extensively in 1982. At the same time, the Uniform Law Commission enacted the Uniform Guardianship and Protected Proceedings Act (UGPPA) as a parallel act, free standing from the UPC, to address only guardianship of minors and adults. The UGPPA was revised significantly in 1997 to update procedures for appointing guardians and conservators and strengthen due process protections for persons who are the subject of guardianship proceedings. The following year UPC Article 5 was amended to align with the UGPPA. As of June 2012, five states, the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands have adopted the UGPPA.

Although less than half the states have enacted UPC Article 5 or the UGPPA, many provisions of state law governing guardianship proceedings are substantially similar across most jurisdictions. Some common elements of guardianship proceedings include:

- Appointment process

- Differentiating between a guardian for the person's personal affairs and a guardian to protect the person's estate or property (which may be called a conservator in some states)

- Ability to serve as guardian of both the person and the property

- Requirement of guardian of person or property to file a bond (may be waived for guardian of the person)

- Requirement to file an initial report on the protected person's personal and/or financial status; the required content of the report is substantially similar in Uniform Probate Code jurisdictions

- Requirement of guardians of the person to file a report of the protected person's general condition, health status, and continued need for guardianship protection, typically annually

- Requirement of a guardian of the estate or property to file a financial accounting, typically annually

- In Uniform Probate Code jurisdictions, the court may appoint a person (visitor) to monitor and report on the condition of the protected person; visitors typically are trained volunteers

- Authority to remove a guardian that is not performing his or her duties to protect the best interests of the protected person.

The Uniform Adult Guardianship and Protected Proceedings Jurisdiction Act (UAGPPJA) is the most recent effort to improve the guardianship process nationwide. The UAGPPJA addresses problems that can arise when the person subject to guardianship proceedings has contacts and or property in more than one state. Jurisdictional conflicts can unnecessarily prolong guardianship proceedings, increase costs for the person and the guardian, and present greater opportunities for abuse and financial exploitation of the person. The UAGPPJA sets out rules for determining which state has jurisdiction over a particular guardianship proceeding at any given time. As of June 2012, 32 states and the District of Columbia have implemented the UGPPJA, and legislation to adopt the UGPPJA is pending in an additional seven states and Puerto Rico.

The American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging tracks legislative action and policy reforms across the states (the 2014 State Adult Guardianship Legislative Update can be found here). In addition to reducing jurisdictional conflicts through adoption of the UAGPPJA, in recent years states have focused on identifying and preventing exploitation of protected persons by guardians and conservators. Legislation in several states has addressed guardianship qualifications and mechanisms to hold guardians accountability. For example, innovations in legislation and court rules in Nebraska require criminal and financial background checks on persons nominated to be guardians and conservators and mandate bond filings by conservators of estates greater than $10,000. Courts also have specified responsibilities for reviewing inventories and accountings and for enforcing compliance with requirements and restrictions placed on guardians and conservators.

Resources

- National Guardianship Association

- Nine Ways to Reduce Elder Abuse Through Enactment of the Uniform Adult Guardianship and Protective Proceedings Act

- Uniform Law Commissioners

How many guardianship cases are there in the United States? To date, we do not have an accurate assessment of the number of open adult guardianship and conservatorship cases. The collection of reliable data is besieged by a number of problems.

Limitations of "Official" Statistics

Generally, the "official" court data at the state level is unreliable or not available. In a 2006 exploratory study of state guardianship data, the ABA Commission on Law and Aging found that many state court administrative offices did not receive information on guardianship from trial courts and noted that the majority of reporting states could not provide state-level data. The problem is compounded by the lack of statewide case management systems that can identify case events for guardianships and conservatorships. The lack of state-level data requires researchers to focus on local courts, the only source of accurate and reliable guardianship data.

Generally, the "official" court data at the state level is unreliable or not available. In a 2006 exploratory study of state guardianship data, the ABA Commission on Law and Aging found that many state court administrative offices did not receive information on guardianship from trial courts and noted that the majority of reporting states could not provide state-level data. The problem is compounded by the lack of statewide case management systems that can identify case events for guardianships and conservatorships. The lack of state-level data requires researchers to focus on local courts, the only source of accurate and reliable guardianship data.

In 2010, the National Center for State Courts, on behalf of the Conference of Chief Justices/Conference of State Court Administrators Joint Task Force on Elders and the Courts, presented results from a survey of judges and court managers on guardianship issues, including the collection of data. The results, compiled in Adult Guardianship Court Data and Issues , confirmed that quality data on adult guardianships continues to be problematic. In particular, courts may have some information on filings, but have more difficulties tracking caseloads, as these cases can remain open for years and sometimes decades.

In 2014, the National Center for State Courts, under a contract with the Administrative Conference of the United States, conducted a survey of adult guardianship/conservatorship court practices. The survey of judges, court staff, and guardians focused on the following topics: selection of guardians, monitoring practices, case management, sanctions and removal of guardians, caseload trends and court outreach. The final report, SSA Representative Payee: Survey of State Guardianship Laws and Court Practices , includes survey findings, a review of state statues on adult guardianships/conservatorships, and a summary of interviews with state adult and foster care agencies.

"Official" court data is collected through the Court Statistics Project (CSP), which is a joint effort by the National Center for State Courts, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and the Conference of State Court Administrators. The State Court Guide to Statistical Reporting offers a consistent, nationally recognized model for bridging the terminology differences among state legal systems and distinguishing these civil case types from each other. A review of the guardianship data indicates:

- Few states report complete statewide data

- Adult guardianships and conservatorships are often not reported as a distinct case type, making it impossible to get an accurate count of these cases

- The data that is reported suggests the trend in guardianships is hard to interpret

- The frequency of guardianship cases among the states varies widely.

Deficiencies in the statewide collection of data on the number of active cases are compounded by the lack of statewide case management systems that can identify key case events for guardianships and conservatorships. Further, some states cannot distinguish between guardianships granted to children, incapacitated young adults, and elders. Finally, the inconsistent use of terminology across states makes the collection of systematic national data challenging.

Calls for Improved Data Collection

The insufficiency of guardianship data has been noted by federal legislator and state courts.

- 2018, Senators Gordon Smith and Herb Kohl, chairs of the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, issued a report on Guardianship for the Elderly that encouraged the collection and review of electronic case data.

- In 2009, CCJ and COSCA passed Resolution 14, "Encouraging Collection of Data on Adult Guardianship, Adult Conservatorship, and Elder Abuse Cases by All States."

- In 2010, the CCJ/COSCA Joint Task Force on Elder and the Courts report included a top recommendation that "each state court system should collect and report the number of guardianship, conservatorship, and elder abuse cases that are filed, pending, and concluding each year."

- Also, in 2010, COSCA selected the topic of guardianships as the focus of their White Paper, which supported national data collection efforts.

A "Best Guess" Estimate of Guardianship Cases

The calls for documentation of guardianship cases have increased while the availability of reliable data has changed little. In 2011, the National Center for State Courts released Adult Guardianships: A "Best Guess" National Estimate and the Momentum for Reform. The report acknowledges current statistical limitations and focuses on data from four states to develop an estimate of 1.5 million active pending adult guardianship cases in the United States. This estimate does not include adult conservatorships, for which data is not available.

Resources

- Adult Guardianships and SSA Representative Payee Program Report

- Caseload Highlights: The Need for Improved Guardianship Data

- Guardianship of the Elderly: Past Performance and Future Promises

- Adult Guardianship Court Data and Issues: Results from an Online Survey

- Adult Guardianships: A "Best Guess" National Estimate and the Momentum for Reform

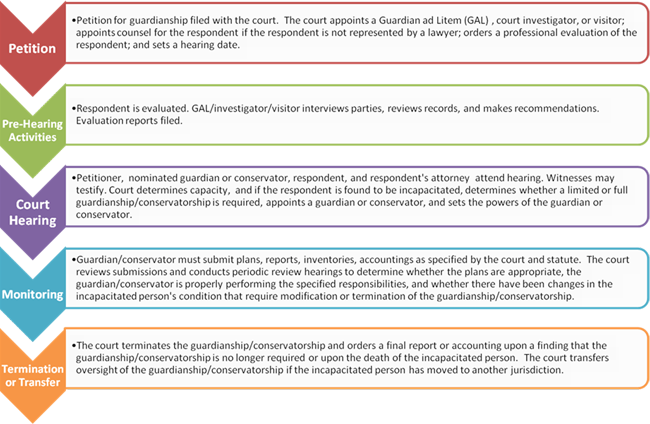

The guardianship process can vary significantly by state, court, and judge. Generally, the process begins with the determination of incapacity and the appointment of a guardian. Interested parties, such as family or public agencies, petition the court for appointment of guardians. The court is then responsible for ensuring that the alleged incapacitated person's rights to due process are upheld, while making provisions for investigating and gauging the extent of incapacity. Should the individual be deemed incapacitated, the judge appoints a guardian and writes an order describing the duration and scope of the guardian's powers and duties. Once a guardianship has been appointed, the court is responsible for holding the guardian accountable through monitoring and reporting procedures for the duration of the guardianship. The court has the authority to expand or reduce guardianship orders, remove guardians for failing to fulfill their responsibilities, and terminate guardianships and restore the rights of wards who have regained their capacity.

Generally, guardianships include five separate court actions: petition, pre-hearing activities, court hearing, monitoring, and termination or transfer. Descriptions of each step follow.